Kern van Raworths betoog

Kate Raworth is een Engelse econome en activiste die na haar economiestudie in Oxford, werkte in Zanzibar, ter ondersteuning van vrouwelijke micro-ondernemers, in New York voor UNDP en vervolgens als campaigner bij Oxfam, om later naar haar vroegere universiteit in Oxford terug te keren met als doel het onderwijs in de economie te hervormen.

De kern van haar betoog is dat markten inefficiënt zijn en groei niet ongestraft kan blijven doorgaan. De draagkracht van de aarde zal moeten worden gerespecteerd en de economie moet alle mensen een waardig bestaan bieden. Ze gebruikt daarbij de metafoor van de donut. Het deegdeel van de donut stelt een duurzame economie voor, het lege hart geeft weer welke sociale tekorten er kunnen ontstaan en de buitenste rand markeert wanneer ecologische plafonds worden overschreden. Dat betekent dat de economie zich aan de sociale en ecologische randvoorwaarden moet aanpassen, ook al zou daardoor de economische groei wat afnemen. Tussen de sociale en planetaire grenzen ligt een milieuveilige en sociaal rechtvaardige, kortom duurzame ruimte waarbinnen de mensheid kan floreren.

In de hele wereld maar ook in Nederland is er meteen aandacht voor haar boodschap. In Follow the Money verschijnt dezelfde maand nog een recensie (Van de Linden, 2017), gevolgd in juli door bijvoorbeeld de Groene Amsterdammer (Engelen, 2017) en in december door Trouw (Bijlo, 2017). In Buitenhof treedt ze 29 oktober 2017 op en op 10 januari 2018 neemt ze bijvoorbeeld deel aan een door Tilburg University georganiseerde Meetup in Paradox te Tilburg.

Nieuw is de verpakking

Gezien deze aandacht moet er wel iets nieuws zijn aan haar boek. Om kort te zijn, dat is naar onze mening niet de inhoud maar de verpakking. De verpakking is de metafoor van de donut, maar de inhoud is een getrouwe kopie van de VN Sustainable Development Goals (2015) die alle regeringsleiders in 2015 ondertekenden. En daar ging een eerdere versie aan vooraf, de Millennium Development Goals stammend uit 2000. En wanneer we nog verder terug gaan (Zoeteman en Tavenier, 2012) dan komen het VN Brundtland rapport over duurzame ontwikkeling ‘Our Common Future’ van 1987 in beeld en de kernboodschap van Meadows’ rapport aan de Club van Rome ‘Grenzen aan de Groei’ uit 1972. Van het laatste boek werden in Nederland alleen al een miljoen exemplaren verkocht.

Te midden van het enthousiasme en de aandacht voor Raworth’ donut-economie moet de vraag gesteld worden of deze tot iets zal leiden dat de afgelopen halve eeuw niet is gebeurd: een omslag in het denken van de gevestigde economen, hun leerboeken en hun invloed op de regeringen en financiële instellingen van de OESO-landen.

Hoe staat het ervoor in Nederland?

Het regeerakkoord van kabinet Rutte III zou het groenste regeerakkoord aller tijden zijn. Maar wie verder kijkt dan de windparken op zee, die door de elektriciteit gebruikende burgers worden betaald, komt tot de omgekeerde constatering: het milieubeleid heeft met dit kabinet haar voorlopige dieptepunt bereikt. Volgens het Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving (2017) worden de klimaatdoelen voor 2030 maar voor de helft gehaald. De aangekondigde stoere maatregelen moeten bovendien vooral worden uitgevoerd door latere kabinetten. Nederland staat bij duurzame energie in Europa onderaan de lijst (Clingendael, 2015). Ook hier worden de doelstellingen niet gehaald, en dat terwijl duurzame energie voor tweederde wordt opgewekt uit biomassa, ofwel met bomen uit Canada en frituurvet uit China. En hoewel bijna alle milieuwetenschappers en de meeste economen het doorberekenen van de milieukosten in de marktprijzen als meest zinnige maatregel zien, komt er geen regulerende CO2-prijs. Daarmee wordt de kans gemist om de economie zich optimaal te laten ontwikkelen binnen de door de aarde gestelde grenzen, het deegdeel van de donut. Dat de aarde grenzen stelt is echter al decennia een doorn in het oog van voorstanders van zo hoog mogelijke economische groei en ook van Rutte III. Er is in Den Haag dan ook weinig goed milieunieuws onder de zon. Naast het opportunistische klimaatbeleid zijn bijvoorbeeld ook de discussies over de milieueffecten van vliegverkeer bij Schiphol en Lelystad dezelfde als 25 jaar geleden (Hermanides, 2017). Door steeds weer nieuwe rekenmethoden te lanceren wordt de discussie eindeloos gerekt zonder harde maatregelen te nemen. Dat geldt ook voor het mest- en afvalbeleid. Al decennia worden dezelfde plannen en technische dagdromen bediscussieerd, terwijl er in de praktijk weinig gebeurt.

Donut of do-not economie

In deze ontwikkelingen tekent zich een patroon af. Door steeds met kleine verfijningen uitwegen te zoeken hoeft er geen fundamentele ommezwaai in beleid gemaakt te worden; de wetenschappers zijn immers nog in discussie! Om die discussie gaande te houden wordt veel oude wijn in nieuwe zakken gedaan en kan intussen het verlangen naar groei ongestoord uitgeleefd worden, totdat er ernstige ongelukken gebeuren, zoals bij de aardbevingen in Groningen. De discussie over de donut-economie kan zomaar afleiden van waar het echt om gaat, het bestendigen van de ‘do not’- economie: we weten het wel, maar we doen het niet.

Dat is helaas zichtbaar in het huidige regeerakkoord, waarbij het klimaatbeleid in Nederland letterlijk en figuurlijk wordt ondergebracht bij, en ondergeschikt gemaakt aan, Economische Zaken. Natuur is al eerder ondergeschikt gemaakt aan landbouw. Die constructies maken duidelijk dat milieubeleid alleen wordt gevoerd voor zover dat economisch pijnloos inpasbaar is. Het regeerakkoord is niet gebaseerd op een donut-economie maar op een do not-economie, waarbij het milieu zich moet voegen naar de economie. De minister van milieu zal daartegen in de kabinetsvergaderingen geen bezwaar maken. Voor het eerst sinds 1971 is die er namelijk niet meer. Het Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu gaat voortaan over Infrastructuur en Waterstaat. Het groene élan is in het Rutte tijdperk dan ook sterk verwaterd.

Het idee van de donut economie heeft echter als verdienste dat het duurzame ontwikkeling makkelijk communiceerbaar maakt. Het vervangt het samenraapsel van de 17 VN Sustainable Development Goals in één samenhangende visie en op een tijdstip dat het Klimaatverdrag van Parijs in werking treedt en het Westen naar een nieuw gedeeld ideaal zoekt. Dit, gekoppeld aan Raworths aanstekelijke enthousiasme en ijver, geeft het praten over de Donut economie vleugels. Echter, alleen een krachtige klimaatwet met meetbare en afrekenbare doelstellingen kan de donut gedachte in de praktijk van het doen en laten in ons land enigszins overeind houden.

Referenties:

Bijlo, E., 2017, Trouw, De verdieping, De nieuwe economie ziet eruit als een donut, 16 december 2017, 14-15

Clingendael, 2015, Duurzame energie in Nederland en de EU, Den Haag.

Engelen,E., 2017, Kate Raworth: iconoclaste van de economie, Verander de wereld, begin met een potlood, Groene Amsterdammer, 5 juli 2017

Hermanides, E., 2017, Actiegroepen, vliegroutes en milieurapportage lijken opening Lelystad Airport te vertragen, Trouw, 20 december,

Meadows, M.D., D.L. Meadows, J. Randers, W.W. Behrens III, 1972, The Limits to Growth, New York NY: Universe Books

Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving, 2017, Analyse regeerakkoord maatregelen brengen helft klimaatdoel in zicht.

Raworth, K., 2017, Doughnut Economics, Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, New Orleans LA: Cornerstone, 6 April 2015

Van der Linden, M. J., 2017, De Donut-economie van Oxford-onderzoeker Kate Raworth, 20 april, Follow the Money.

VN Brundtland rapport, 1987, Our Common Future, Oxford: Oxford University Press

VN, 2015, UN Sustainable Development Goals, New York.

Zoeteman, K., J. Tavenier, 2012, A short history of sustainable development, in: (K. Zoeteman Ed.) Sustainable Development Drivers, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, Chapter 2, 14-54.

Comment by Kate Raworth on Zoeteman and Van Egmond

Thank you both for taking the time to review and discuss my book, I

sincerely appreciate that. I like your contrast of the donut economy to the

do not economy. I'd just like to clarify a couple of points.

First, the doughnut is by no means a copy of the SDGs. It was first

published in early 2012. The SDGs were agreed in late 2015. In fact the

doughnut was literally on the negotiating table in the late night final

sessions of finalising the SDGs, there to remind negotiators of the big

picture vision they were aiming for. It is also not a copy of the MDGs: the

centre certainly reflects many similar goals (it would be very odd if it

did not) but as you no doubt know, the MDGs were almost silent on

environmental issues

Second, is this just old wine in new bottles? Well Andre Gide put it best.

"Everything that needs to be said has already been said, but since no one

was listening, it has to be said again." At the same time, I am not really

one to toot my own trumpet but I invite you to show me one other book, or

even one other diagram, that combines ecological economics, feminist

economics, complexity, institutional and behavioural economics into one

coherent story.

Reply by Zoeteman and Van Egmond

January 18, 2018

We thank Kate Raworth for replying to our (Dutch) comment on Doughnut

Economics. Our article was mainly directed at Dutch policy

makers. We stated that the environmental policy in this country changes

from a doughnut economics to a ‘do not’ economics: everything is

subordinated to (neo-liberal) economics. In this reply we could not resist giving some extra comments on the doughnut idea of Raworth.

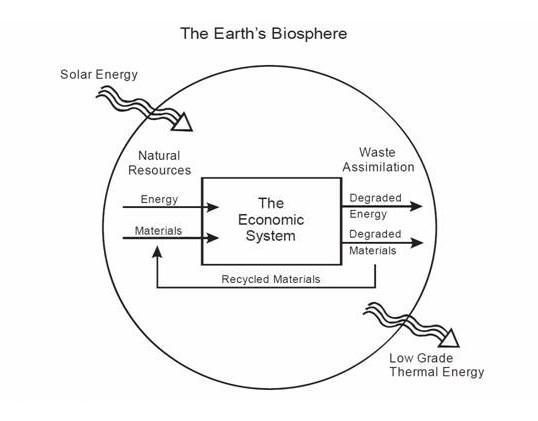

The doughnut model, in which the economy develops within the boundaries of

the ecological carrying capacity is more or less the first law of

environmental sciences. It is called ‘strong’ sustainability, in contrast

to ‘weak’ sustainability in which the economy may grow at the cost of

environment and society as long as the overall outcome is considered

positive. The idea of the concentric circles goes back to the work of

Herman Daly (1973, 1989) and builds on the work of Dennis Meadows (1972)

with respect to the limits to growth. It has been applied in many studies

since then. It is also known as ‘the Russion Doll’ because of its nested

structure in which economy fits in society and society fits in turn in the

ecosystem. One of the earliest and most iconic forms of the picture is

given here:

Source: Ecological Economics, wikipedia

This idea was also applied in the 1989 Environmental Outlook of the Dutch

National Institute for Public Health and Environment (RIVM) called Concern for Tomorrow. Herein the ecological boundaries for the

global system were quantitatively assessed and subsequently used as policy

goals by the government.

Also the UN has been struggling for decades to align the development

policies (focusing on Official Development Assistance to countries and the

establishment of the UN Development Program in 1965) and the environmental

policies (based on the Limits to growth study of Meadows and the Stockholm

Conference on Human Environment of 1972). But gradually these two movements

converged. Important milestones were the earlier mentioned work of Daly and

later of Stivers (1976), Bossel (1977) and Max-Neef’s work for the Human

Development Index. The Millennium Development Goals of 2000 and SDGs of

2015 are advancing this fusion process as does the concept of Doughnut

economics. Our general statement is that all these ideas, including the

Sustainable Development Goals, originate from the earlier notions of

‘limits to growth’ and the many studies that have been appeared since then.

As environmental scientists we have become rather disappointed about

economists in the policy debate on economic growth and the environment over the

last 40 years. The (general equilibrium) models they were erroneously using

in environmental decision making are now discredited in peer reviewed

scientific journals, as there is never equilibrium in the real world and

money is not included in the models, as pointed out by Minsky (1986). The

current disconsolate state of environmental policy in the Netherlands and

elsewhere is to a large extent the result of discrediting the (‘donut-)

concept of ‘strong’-sustainability, replacing it for ‘weak’-sustainability.

This was advocated by the majority of economists and their so-called ‘broader view on

welfare’, in which the environment was also included. In this view, the

growth of the economy in spite of the environment can be motivated by

societal cost-benefit-analysis, in which arbitrary choices were made

concerning rates at which the future was discounted. So now there was a

claim from the economists about ‘a new economic paradigm’ we could not

resist toto give our view on how Doughnut Economics fits in with this

so-called consensus among (environmental) economists.

Of course, Kate Raworth’s fresh reformulation of the above mentioned earlier

paradigms (all going back to the ‘limits to growth’ ) will create

awareness of the sustainability problem among the current generation and

generations to come. But it can, and to our opinion will be used as a

motive to further delay policy making. The ‘new’ reformulation suggests

that we apparently did not understand the problem well, so we have to

restart the policy process all over again. This requires new debates and

new policy developments, thus losing decades for taking timely action.

Given the current policy reactions to Doughnut Economics we fear that this

again will be welcomed as a general reset-button: "now we have found the

real solution and are going to prepare for action (which will take some

time)". One of the many examples of this process is the so-called ‘circular

economy’. In the first 1989 Dutch policy plan, one of the three main lines

was ‘Closing material cycles’. In the 1990’s it was reformulated as the

concept of ‘From cradle to cradle’ and nowadays it is called ‘Circular

Economy’. Meanwhile nothing changed and no significant policy measures have

been taken. But the ongoing sustainability debates misleadingly suggest that

policy actions have been taken.

So, we find ourselves in a paradoxal situation. On the one hand we

appreciate Kate Raworth’s efforts to communicate essential insights in the

language of the current generations. On the other, we are afraid that,

beyond her control and intention, the suggestion of new insights will be

welcomed as a convenient excuse to restart the policy process all over

again.

References

Bossel, H. (1977) Orienters of non-routine behavior, in H. Bossel (ed.): Concepts and Tools of Computer-assisted Policy Analysis, Basel:

Birkhäuser, 227-265

Daly H., Toward a Steady-State Economy (1973),

Daly H. and J. Cobb Jr (1989) For the Common Good, Redirecting the Economy Toward Community ,

Boston MA: Beacon Press

Meadows, D.H, D.L. Meadows, J. Randers, W.W. Behrens III (1972), The Limits to Growth, New York: Universe Books

Max-Neef, M. (1995), Economic Growth and Quality of life, Ecological Economics, 15, 115-118.

Minsky , H. P., 1986, Stabilizing an unstable economy, Hyman P. Mynsky Archive, Paper 144.

Stivers, R. (1976), The Sustainable Society: Ethics and Economic Growth, Philadelphia,

PA, Westminster Press.